When Ivan came home to visit last summer, we decided to have an adventure. This adventure started, as they usually do, with a small smackerel of something.

This case of delights is in the Pittsford Dairy, where they also keep many other delights such as fresh milk in glass bottles, tubs of wholesome-looking butter, ice cream, and loaves of apple strudel bigger than your head (which is the appropriate size for apple strudel).

After the Pittsford Dairy, we went on our way to the Jell-O Museum, which is about an hour away in LeRoy. We didn't know what to expect. What is there to discuss about Jell-O, really? It's Jell-O. So we were unprepared for the bizarre and delightful experience that we ended up having.

We made guesses beforehand on the ratio of old gentlemen to old ladies behind the counter, and we were both wrong: it was one elderly woman and her granddaughter. The elderly woman took us to the entrance of the museum, sat us down on a bench, and gave us an incredibly charming oral history of Jell-O and the museum. You could tell that she had given this history many, many times, simply because it was so polished, but she still enjoyed making the jokes and still laughed at them. Ivan and I were thoroughly won over. The entire museum was like that: it looked like very dedicated people who really cherished Jell-O had gotten together, raised a bit of money, and put together a pretty decent museum with whatever artifacts they could get their hands on, and construction paper.

It turned out they could get their hands on quite a lot, most of which was advertising. That sounds boring, but it was a fascinating lesson in graphic design during the last hundred or so years. Because they used painting in advertisements, there were a lot of really lovely still lifes . . . of Jell-O. Jell-O is such an odd substance, I found it impressive that it was so nicely rendered. I would put this on my wall, no joke.

What's hilarious about these paintings is how they make it look like Jell-O was the center of American culture. Of course all advertising wants to depict its product that way, but for some reason the fact that it's Jell-O is particularly absurd to me. For example: behold this Eskimo bringing his hard-won Jell-O back to his igloo.

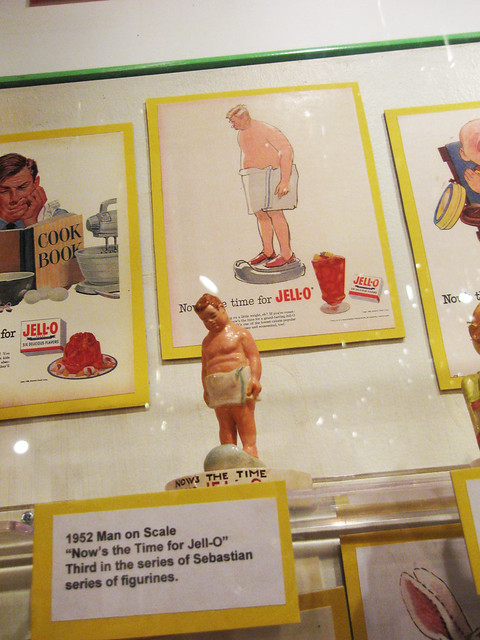

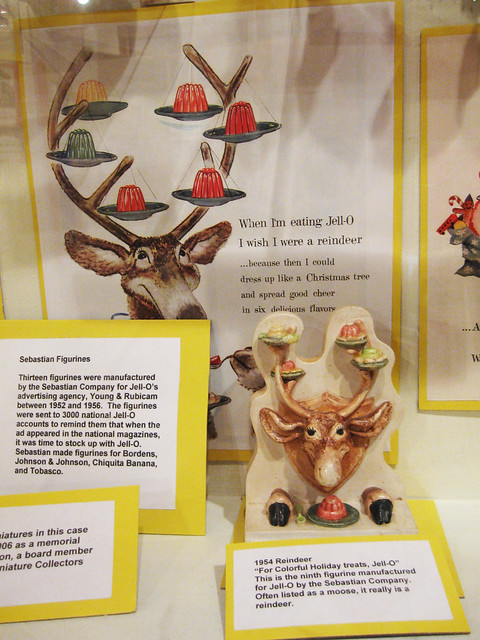

Then again, maybe Jell-O actually was at the center of American culture, because the Jell-O company thought it was a good idea to make these little figurines based on the ads that are pictured in the background.

I wish there had been a figurine for this ad, but I don't think they had it.

One of the best parts was a notebook where people could write down their stories about Jell-O. Ivan and I really liked this one:

"The year was 1982 and I had to come up with a model of a plant cell. Overnight, my sister and I made the model out of Lime Jell-O & mints & pieces of licorice. I told the class it was edible & my science teacher gave me a spoon and & told me to eat."

There was also this brief tale about Jell-O salesmen:

"As I recall, I was with the Jell-O company in 1915, and was on the last wagon that they had in operation. . . . The salesman was an ex circus man. He was delightfully tough and remarkable for his ability to wear a derby hat on the side of his head, even while eating, and for his knack of chewing tobacco and smoking a cigar at the same time. . . . We covered Ohio south of Columbus, hitting towns of 2500 and under. Most of them were under. We started in Xenia on Thanksgiving and worked through the winter, which was probably the ghastliest, coldest job that ever existed outside the trenches. . . . While driving through the country, we were supposed to tack up big canvas signs. This was a sporting proposition, as farmers were never much in favor of the idea. We were shot at several times by outraged natives but only once with any effectiveness. The bird shot was removed from the salesman at the next town, and the operation was charged up as a veterinary fee. (Repairs on horses were a legitimate expense--but not repairs on salesmen.) [Excerpts from "On the Wagon," by Sid Ward, General Foods Magazine, 1931.]

In addition to these strange and wonderful stories, they also had strange and wonderful old Jell-O flavors that have been discontinued. Did I say wonderful? I meant horrifying and revolting.

Arguably, the best part of the museum is when you turn a corner and suddenly you see this:

This is a giraffe. Why? WHY NOT.

It so happens that this giraffe was part of a visiting circus near LeRoy when it suddenly expired, and since Jell-O had had an ad campaign involving giraffes, the obvious solution as to what to do with the giraffe carcass was to stuff it and give it to the Jell-O museum. Possibly it was dissected first by the local doctor -- I might be mixing this up with a novel I read once, but it might also have happened for real with this giraffe. I am uncertain and in cases when facts are uncertain I report them anyway just in case they're true. This is known as responsible journalism.

With this, our visit to the museum came to the end.

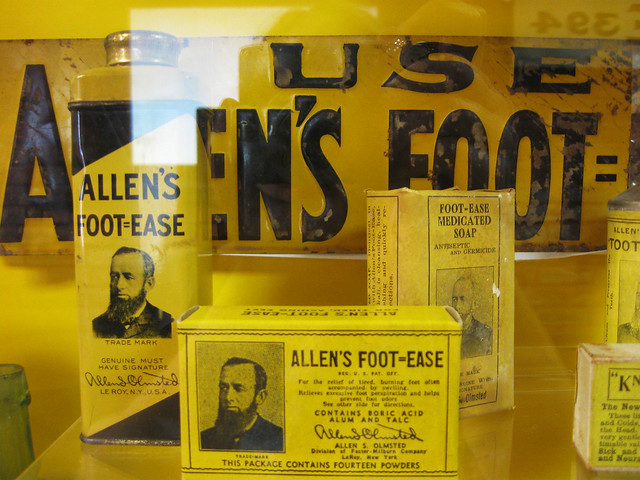

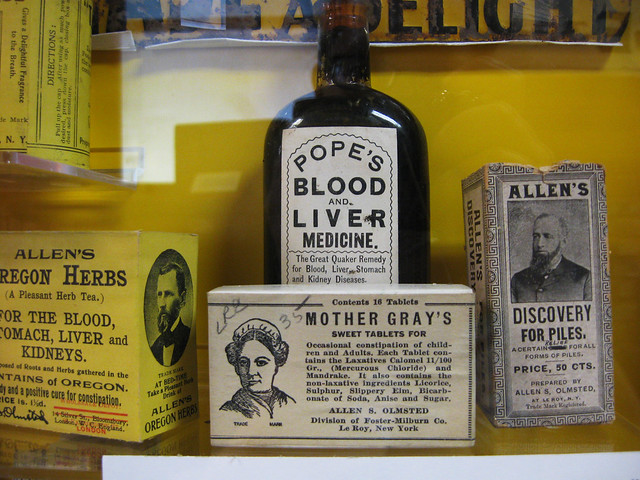

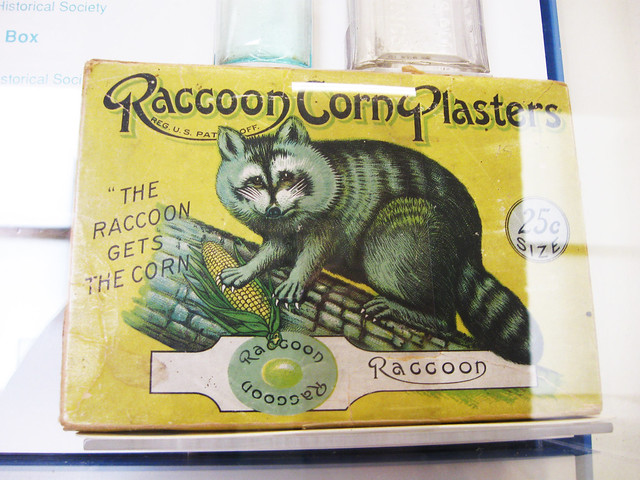

BUT DID IT REALLY? NO IT DID NOT. It turns out that in the basement of the Jell-O museum is a small museum of transportation, and a collection of old medicaments that made me grateful that I was born no earlier than I was, for raccoons seem to be too much involved for my personal taste. Part two of our trip to what I am now referring to as the LeRoy Museum Complex will be covered in the next post. I will also quote at length from a moral poem about vanity and outdoor safety, so you won't want to miss THAT.